The Christ the Redeemer in Art

The Enigma of the Face of Christ

The face of Christ, for the past two thousand years, has represented an enigma that no one has ever been able to, nor will ever be able to, fully unravel. The Shroud of Turin (1) remains the only reliable document in this regard.

However, the Shroud, while providing an extremely evocative image, cannot certainly be taken as an example of a formal model. Personally, I believe it is absolutely worthy of faith, but from there to draw inspiration for a pictorial definition, it doesn’t seem at all possible. Unless one wants to stylize it or subliminate it in some way. In fact, however, such an attempt would represent the face of the Shroud, not the face of a man.

It does not maintain all those formal references necessary to provide a faithful representation. It is, in itself, a sublimated image, furthermore in negative.

Needless to say, throughout history, there have been many attempts to reconstruct the face of Christ, and none of them have taken the Turin Shroud as a model. Apart from the Shroud, there have been exceptional cases where men and women, religious and non-religious, have indeed claimed to have seen the face of Christ.

The morphology of a young man with light eyes, a sparse beard, and blonde-reddish hair is the one that has most strongly impressed over the centuries. The Polish mystic Faustina Kowalska, canonized by Pope John Paul II, and to whom the famous Divine Mercy Sunday, the first Sunday after Easter, as the feast of Mercy, was dedicated, ordered a painter to portray an image of Jesus, known as “Divine Mercy” (2), with whom she conversed almost daily.

The painting, done life-size, is very beautiful and exudes a grace and generosity that is uncommon. It is venerated worldwide and can be said to represent more than adequately the love and mercy of the Redeemer toward mankind.

Unfortunately, the same nun initially claimed that it was not accurate and that the image did not perfectly match the features of the mystical figure, as the transcendental entity with whom she had repeated visions, was, according to her, much, much more beautiful than the painted one.

Needless to say, the painter who was commissioned to create the work had to endure much criticism, and perhaps even some reprimands from the Saint.

We should have asked Padre Pio to give us a description of Jesus’s features. However, I doubt he would have responded affirmatively. In his writings, he describes him in many different ways, often speaking of a singular figure all in white and excessively radiant.

Indeed, this seems to match. Similar cases, in which camera films or accidental paintings have appeared in the sky, are not rare. The problems that painters face when attempting to paint and therefore structure the sacred face have, perhaps rightfully or perhaps wrongfully, never really drawn from these exceptional cases.

The artist’s attempt is to structure a face, not necessarily the same as that of the original visions, but one that embodies a personal representation, new and possibly broader than previous references, aiming to expand rather than deepen the horizons of the collective imagination regarding the figure of Christ.

The goal is not to describe the Holy Face, but to evoke in the observer the emotion, the suggestion that can arise from it. In this sense, the attempt fits well within the direction of contemporary art. Not to describe, but to represent: not to identify, but to induce, to evoke emotion and presence.

Whether starting from a true transcendental vision, or even from the face of the Shroud itself, I don’t know to what extent this can fit into this purpose. Surely it could be an option, but in general, it has not been the path taken by many painters to date.

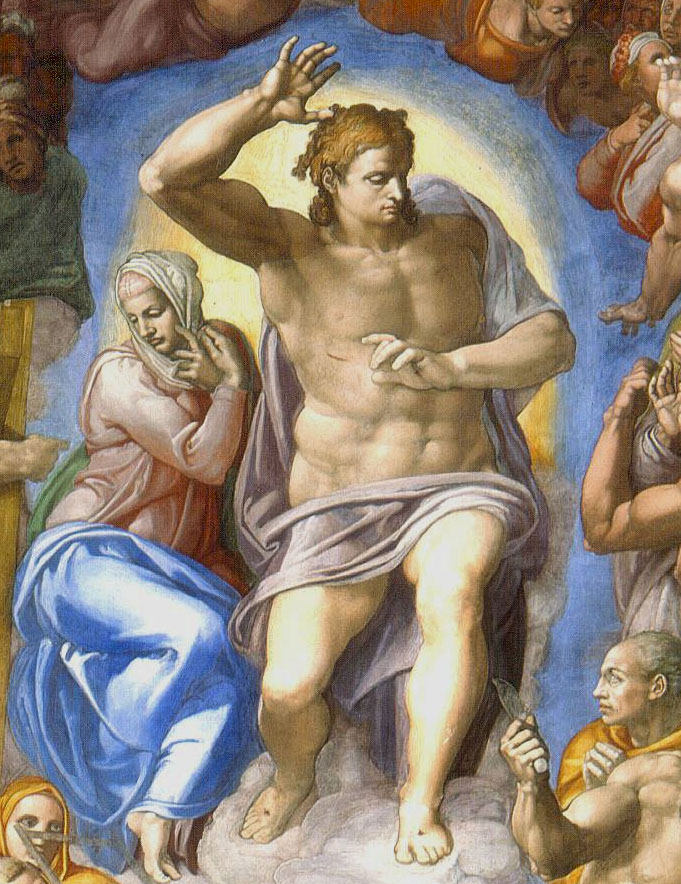

The figure of Christ in Michelangelo’s Last Judgment (3) undoubtedly has an exceptional power and strength, even though it does not correspond at all to the absolutely virtuous models, and probably more faithful to the mystical tradition.

Christ in Dalí’s work, on the other hand, specifically derives from a portrait of the mystical vision of St. John of the Cross. The case seems exceptional, since the Spanish mystic, besides being a doctor of the Church, had an exceptional talent for drawing, so the original painting itself is a work of art of the highest importance.

Dalí drew great inspiration from it without straying at all from the original. But not all mystics, can hold a brush in their hand! That task should be left to the painters…

Trivially, one could say that Christ does not have a specific face, but has many aspects; or even that he simply has the face of every man.